100 years ago: Wet or dry? Liquor fracas shaped 1915 Legislature

The mounting grassroots pressure for Sunday liquor sales that made itself felt at the Capitol last year has already spawned a raft of related legislation in 2015. So far, members of the Republican majority have introduced six bills on the subject in the House.

Leading the way is Rep. Steve Drazkowski (R-Mazeppa), who has offered three variations on a theme: a full repeal of the Sunday sales prohibition (HF115), a measure to allow municipalities to opt into Sunday sales (HF130), and a proposal to launch a Sunday pilot project in Anoka, St. Louis and Winona counties (HF131).

“It’s really about free markets,” Drazkowski said. “It makes about as much sense not to allow liquor to be sold on Sundays as to not allow bread to be sold on Mondays or tires on Tuesdays.”

Drazkowski credits public engagement on the issue for his newfound sense of optimism, but he knows any such move will continue to elicit fierce opposition from its two perennial foes – the Minnesota Licensed Beverage Association, which represents liquor retailers, and the Teamsters Union, which fears the move could cause its contracts with liquor suppliers to be reopened.

No matter what becomes of the Sunday sales push in 2015, however, the fireworks are sure to fall short of the liquor-generated drama of the 1915 Minnesota Legislature, when distilling interests engineered a victory in the battle over the speakership of the House only to lose the war to keep Minnesota a mainly wet state.

Alcohol the ‘one vital question’ of election

St. Paul's lavish Ryan Hotel served as a base of operations for the pro-liquor lobby as it battled to defeat a bill that promised to restrict the sale of alcohol around the state. (Photo courtesy Legislative Reference Library)

St. Paul's lavish Ryan Hotel served as a base of operations for the pro-liquor lobby as it battled to defeat a bill that promised to restrict the sale of alcohol around the state. (Photo courtesy Legislative Reference Library)Though national Prohibition – whose enabling legislation would bear the name of Minnesota Republican Congressman Andrew Volstead – still lay six years away, the temperance issue loomed large in Minnesota’s 1914 state elections. In his book, “The Minnesota Legislature of 1915,” St. Paul Daily News government reporter Carl J. Buell called it the “one vital question” hanging over the campaign.

At issue was whether Minnesota would continue as a state that allowed each municipality to set its own liquor policy or adopt a system known as “county option.”

Under local option, Buell wrote, “The farmers who occupy the surrounding country are wholly shut out from any voice in the matter; yet they must come [to town] to trade; their older children must go there to school; and there is the social center where they must seek entertainment and religious and moral instruction….

“The whole county must pay the cost of prosecuting the criminals and supporting the paupers that result from the legalized saloon. Why, then, should not all the people of the county be allowed to vote on the question of licensing saloons within its borders?”

In an age when farming remained a very labor-intensive proposition, the rural population accounted for 59 percent of Minnesota’s 2 million residents as of the 1910 U.S. Census, and the proportion was greater still outside the immediate vicinity of Minneapolis and St. Paul. So the specter of county option promised to put most of the state squarely in the dry column. And the results of the 1914 election left little doubt that allies of the Anti-Saloon League had won working majorities in House and Senate alike.

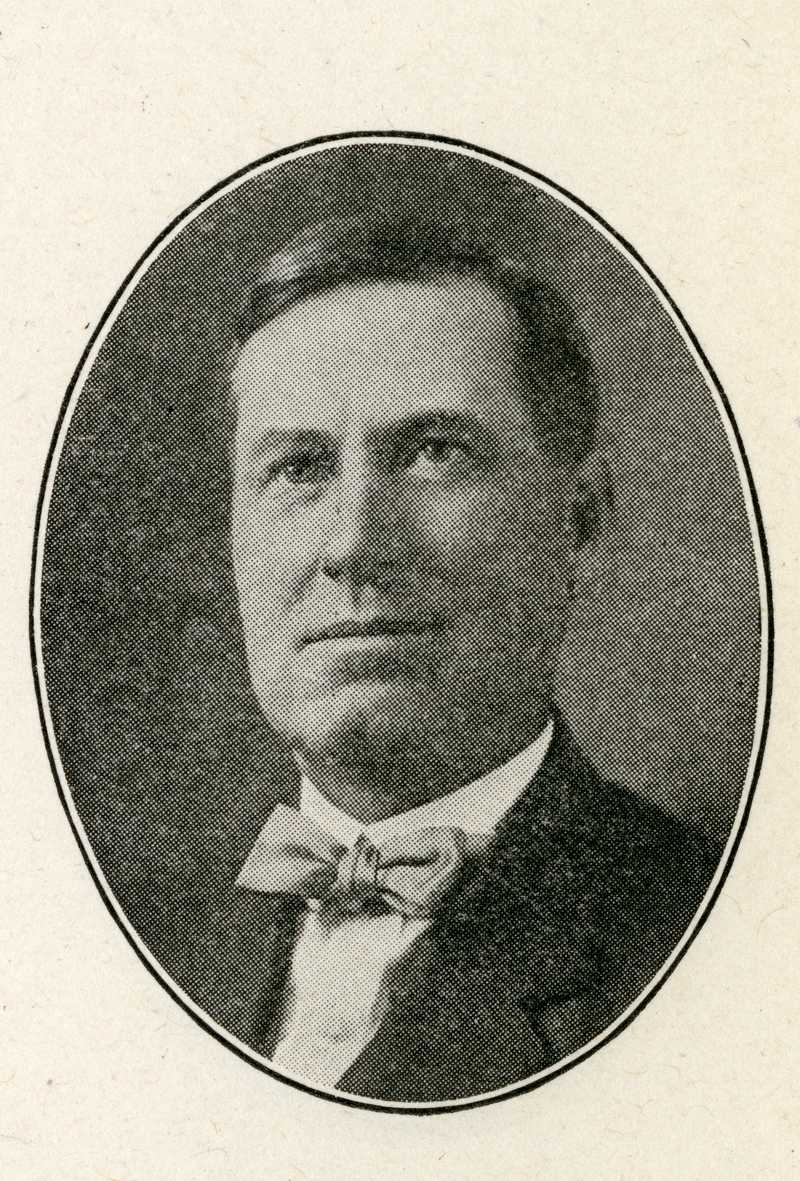

Rep. J.H. Erickson of Clinton became the first of three defectors who abandoned the "dry" candidate for speaker when the 1915 session convened. He was later named chair of the House Banks and Banking Committee. (Photo courtesy Legislative Reference Library)

Rep. J.H. Erickson of Clinton became the first of three defectors who abandoned the "dry" candidate for speaker when the 1915 session convened. He was later named chair of the House Banks and Banking Committee. (Photo courtesy Legislative Reference Library)That scenario touched off a furious scramble among liquor interests to build a fire-break around the local option system then in law. According to Buell, the influencers who sprang into action on their behalf included a former Republican lieutenant governor, Edward Smith, and “agents of the Northwest Telephone Co.” Buell offers no explanation of the telephone company’s interest in the alcohol issue.

The ranking eminence among the pro-wet lobbying corps was Edward Claggett, a political operative and patronage seeker of considerable renown in his time. A former Mille Lacs County sheriff, he served as sergeant-at-arms during the first legislative session held at the current Capitol, which opened in 1905. Claggett was subsequently appointed superintendent of the State Capitol Commission, but that came to a bad end: He was compelled to resign that post after he was identified as the author of a “slanderous pamphlet” (Buell’s words) about then-Gov. John A. Johnson during the 1904 gubernatorial campaign ultimately won by the Democrat Johnson.

By 1914, Claggett was the distributing agent for the Hamm Brewing Company in Austin, Minn. After the election, Buell writes, Claggett beat a path to St. Paul, where he “took a fine suite of rooms at the Ryan Hotel,” a palatial edifice at 6th and Robert streets downtown, and began to wheel and deal.

Wets won battle for speaker

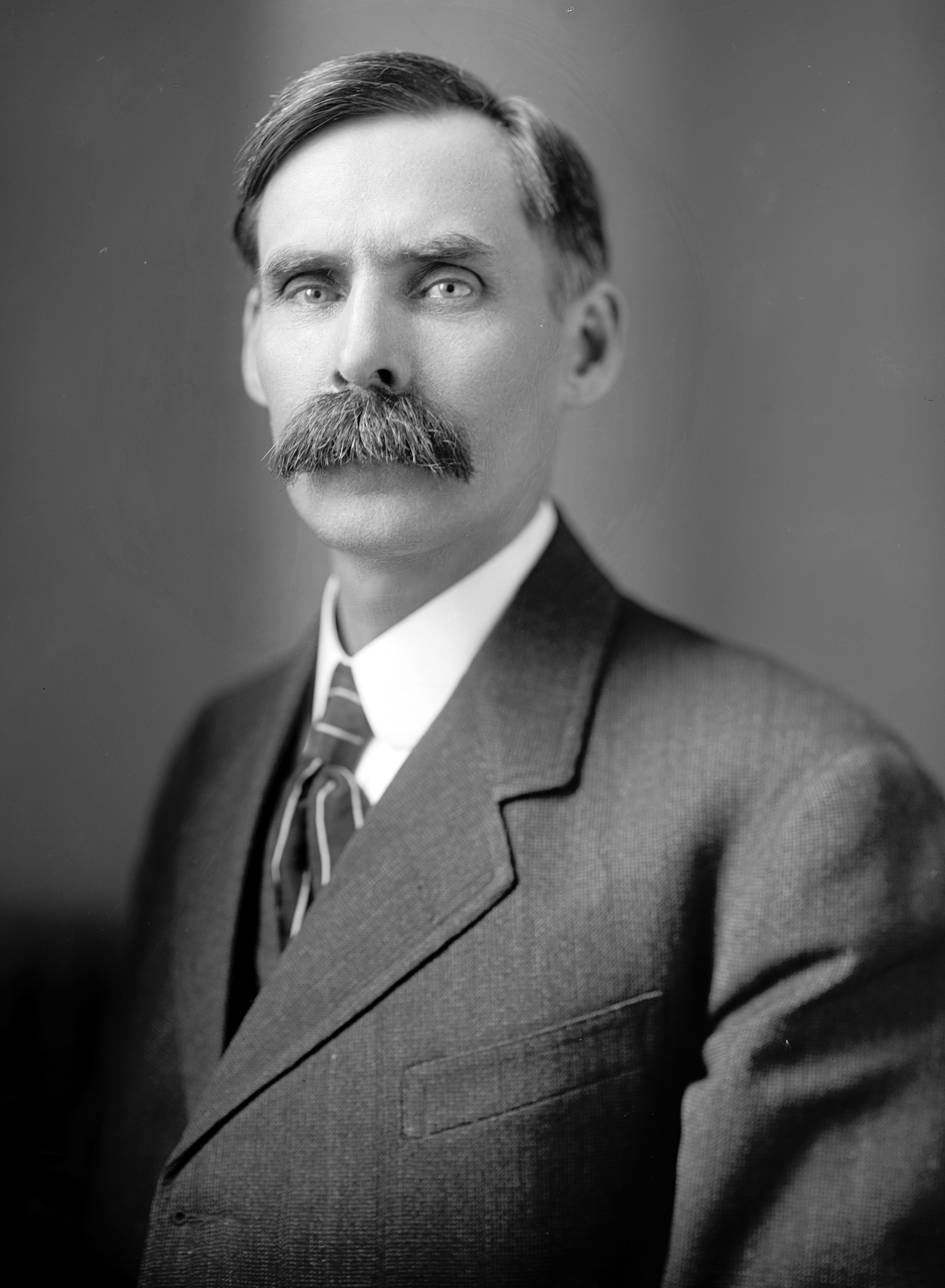

Temperance crusaders rallied around Rep. Sam Gordon of Brown's Valley in the race for speaker. (Photo courtesy Legislative Reference Library)

Temperance crusaders rallied around Rep. Sam Gordon of Brown's Valley in the race for speaker. (Photo courtesy Legislative Reference Library)Claggett and his colleagues decided to make their stand on the selection of a wet-friendly House speaker. They chose as their standard-bearer a second-term member, Rep. H.H. Flowers of Cleveland, Minn. Seeing what the liquor interests were up to, pro-Temperance House members likewise moved to rally around a single figure, Rep. Sam Gordon of Brown’s Valley.

The composition of the House following the 1914 election seemed to favor Gordon, but both sides spent the two-month interlude between the November election and the start of session trying to win votes for their man.

Claggett and company did their jobs well. When the House convened to elect a speaker on Jan. 5, 1915, what appeared to be a narrow majority for Gordon began to come apart during nominating speeches. Rep. J.H. Erickson of Big Stone County, a pledged supporter of Gordon, instead spoke to second the nomination of Flowers.

Buell, who was present on the floor for Erickson’s about-face, described his demeanor that day: “Mr. Erickson was evidently much disturbed in mind, for his face was flushed, he trembled in every part of his body, he neither looked up nor to right or left, but sat in his seat during the rest of the day’s session like one in a dream.”

Buell went on to note that Erickson, an employee of the First National Bank in Clinton, Minn., who was serving his first and only term, was subsequently made chair of the committee on banks and banking.

One more Gordon supporter defected on the first ballot for speaker, and then another on the second. It was enough to hand the speaker’s gavel to Flowers and the wets.

County option prevailed anyway

But if distilling interests proved more than capable at arm-twisting, they erred in their judgment that a hand-picked speaker would prevent House passage of the county-option bill. A month later, the bill cleared both chambers by relatively close votes: 36-31 in the Senate, 66-62 in the House. It was signed into law by the state’s newly elected governor, Winfield Scott Hammond, in February.

After the 18th Amendment made Prohibition the law of the land, Minnesota Congressman Andrew Volstead sponsored the federal enabling legislation. It took effect on Jan. 16, 1920. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress)

After the 18th Amendment made Prohibition the law of the land, Minnesota Congressman Andrew Volstead sponsored the federal enabling legislation. It took effect on Jan. 16, 1920. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress)The new law allowed counties to call special elections on the liquor question by collecting signatures from area voters. The ballot question was simple: “Shall the sale of liquor be prohibited?”

Though the threshold was relatively high – petitioners had to amass signatures equivalent to 25 percent of the ballots cast for governor in their counties in the preceding election – 56 Minnesota counties would go on to vote on the issue before the year was out.

Forty-five of the 56 counties opted to go dry.

By the time the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution made prohibition the law of the land in January 1920, every Minnesota county had voted on liquor. Sixty-four opted to go dry, while 22 stayed wet. The state’s 87th county, Lake of the Woods, would not be incorporated until 1922.

According to the January 1919 edition of the journal Progress (formerly Temperance), that left 87 percent of the state’s geographic territory – though just 47 percent of its populace – on dry ground.

Sources:

Buell, C.J. The Minnesota Legislature of 1915 (no publisher or publication date listed)

Curtiss-Wedge, Franklyn. The History of Mower County, Minnesota (Chicago: H.C. Cooper, Jr., & Co., 1911)

Helmes, Winifred G. John A. Johnson: The People’s Governor. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1949)

Pickett, Deets, ed. The Cyclopedia of Temperance Prohibition and Public Morals (1917 edition) (The Methodist Book Concern)

Progress (formerly Temperance): A Monthly Journal of the Church Temperance Society. January 1919.

1910 U.S. Census

Related Articles

Search Session Daily

Advanced Search OptionsPriority Dailies

Ways and Means Committee OKs proposed $512 million supplemental budget on party-line vote

By Mike Cook Meeting more needs or fiscal irresponsibility is one way to sum up the differences among the two parties on a supplemental spending package a year after a $72 billion state budg...

Meeting more needs or fiscal irresponsibility is one way to sum up the differences among the two parties on a supplemental spending package a year after a $72 billion state budg...

Minnesota’s projected budget surplus balloons to $3.7 billion, but fiscal pressure still looms

By Rob Hubbard Just as Minnesota has experienced a warmer winter than usual, so has the state’s budget outlook warmed over the past few months.

On Thursday, Minnesota Management and Budget...

Just as Minnesota has experienced a warmer winter than usual, so has the state’s budget outlook warmed over the past few months.

On Thursday, Minnesota Management and Budget...